The retrofit agenda: carbon, cost or quality?

Ed Green and Simon Lannon, Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University, explore how to tackle high energy bills and carbon emissions through a smarter approach to retrofit in UK homes.

Recent changes to the cost of energy in the UK have dramatically increased fuel bills for everyone; NEA estimate that 45% of Welsh households are now in fuel poverty (2023). Meanwhile, housing produces 20% of UK carbon emissions (ONS, 2024). The Climate Change Committee have stated that the UK will not meet international, legally binding emissions targets “without near complete decarbonisation of the housing stock” (Rowe and Rankl, 2024). And the social housing sector is expected to lead the way - but cost, complexity and risk all discourage retrofit, particularly for older, ‘hard to treat’ homes. How do we take advantage of the opportunities that retrofit on this scale presents, and improve a housing stock routinely described as the “worst value for money of any advanced economy”? (Guardian, 2024)

Retrofit for carbon

Decarbonising dwellings in the UK typically involves replacing a fossil fuel heat source such as a gas-fired boiler with an electric heat source. Standing charges are now a considerable portion of energy costs, so moving to a single energy source saves the billpayer money, incentivising decarbonisation. But retrofit that focuses solely on decarbonisation is likely to increase fuel bills overall, because heat from mains gas is considerably cheaper than heat from electricity. Early research highlighted this tension. In response, Welsh Government’s decarbonisation policy requires that retrofit balances these two concerns: carbon and cost.

Retrofit for carbon and cost

Deep (fabric first) retrofit enables decarbonisation without increasing fuel costs. However the sequence of works must be planned carefully, or the transition to electric heat will still be seen as an increase in fuel bills. Deep retrofit that includes renewables can dramatically reduce fuel bills, keeping households out of fuel poverty as energy costs continue to rise (reflecting the cost of decarbonising the energy supply network). If renewables are combined with energy storage (typically PV with batteries), fuel bills are even lower, and retrofit can bridge the performance gap between newly built and older homes. Battery storage also reduces pressure on energy infrastructure, which will be increasingly important as the scale of decarbonisation increases.

Retrofit for carbon, cost and quality

Some homes and neighbourhoods are compromised by issues that will not be resolved by a retrofit focussed on reducing fuel The retrofit agenda: carbon, cost or quality? Ed Green and Simon Lannon, Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University, explore how to tackle high energy bills and carbon emissions through a smarter approach to retofit in UK homes. 21 bills and decarbonisation. The directive to decarbonise can (if not managed carefully) override other concerns which are sometimes more important. Retrofit that goes beyond improving technical performance may fundamentally improve the quality (and value) of a home, whether that quality be spatial, functional, cultural or experiential.

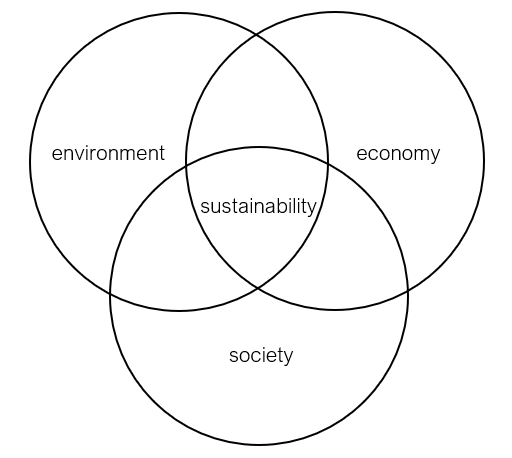

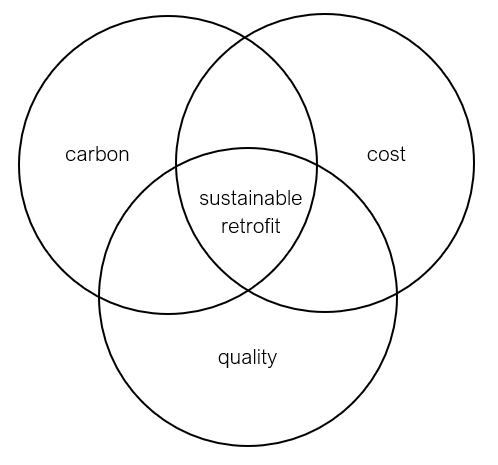

Three long-serving ‘pillars’ of sustainability (diagram below) can be adapted to describe sustainable retrofit. The Venn diagram reflects the importance of a balanced and holistic approach to “carbon”, “cost” and “quality”, despite the fact that carbon and cost are easy to measure, whereas quality is much more difficult to quantify, and tends to be forgotten.

Making retrofit happen

The British Standard for Retrofitting Dwellings (PAS2035) is a method for making retrofit happen. A retrofit specification and the Retrofit Coordinator role are outlined. However a systematic ‘tickbox’ retrofit approach may miss project-specific opportunities to improve quality. Improvement of quality and value are key catalysts for retrofit in the private sector. For this to happen, retrofit that improves quality must be linked to retrofit that decarbonises and improves energy efficiency.

For many homes, retrofit options are constrained (typically by the planning system), limiting opportunities to improve quality. In more constrained situations, recognising and realising opportunities to improve quality requires specialist expertise. Homeowners and landlords also have difficulty comparing the relative merits of different retrofit options, as there are many complex and interconnected factors to consider. (For example, analysis of embodied carbon, which is in its infancy, is likely to discourage demolition and encourage retrofit). Tools must be developed that encourage better decision-making. Support must be provided so that hard-to-treat properties are improved, not neglected or offloaded onto the private sector. Identifying opportunities to improve the quality and long term value of our homes is an important part of successfully decarbonising the whole housing stock.

Retrofit and governance

Governance could create a context for more, better retrofit. Centrally provided guidance for homeowners and landlords would increase the amount and quality of retrofit, particularly in an economic climate where fewer people are moving home. Advice should come from a reputable public body without commercial bias. It should outline a streamlined retrofit process, and describe benefits and challenges clearly so that retrofit is undertaken in an informed way.

The planning process presents a major obstacle for retrofit, particularly if the aim is to increase property value. Permitted development rights enable some work, but the extent can be unclear. Currently it is difficult to obtain meaningful advice on planning matters, partly because every retrofit is different. Local Authorities could reduce risk and uncertainty by providing affordable, accessible advice, project by project. However this would require considerable investment.

Understanding the impact of retrofit on energy performance is essential, and could be a real incentive in the private sector as fuel bills continue to rise. Presently, energy modelling tends to happen too late to inform the scope of work. A coordinated energy efficiency advisory service, aligned with funding for energy efficiency measures, could pump-prime retrofit. This service could deliver best practice advice through exemplar case studies and useful, project specific guidance at the right points in the retrofit process. This would increase confidence in retrofit, diminishing risk and reducing the likelihood of project failure.

Finally, central government, Local Authorities or professional accreditation bodies could make retrofit more attractive and cost effective by incentivising collaboration between retrofit designers and constructors. If design and construction services were offered in a joined up way, either through a one-stop-shop or a partnering approach, there would be less abortive work, shorter retrofit timelines, and better decision making throughout the process.

“Homes of Today for Tomorrow” is a series of four research projects undertaken on behalf of Welsh Government (2017-2024). The Stage 4 report is available here.

Ed Green presented at the APSE Online Social Housing Seminar on Thursday 20 March, his presentation can be viewed on the APSE website.

References

Guardian article: UK housing is ‘worst value for money’ of any advanced economy, says thinktank (25 March 2024)

Office of National Statistics (ONS) collection: 2022 UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions (DESNZ, 2024)

National Energy Action (NEA), summary: Fuel Poverty in Wales (NEA website, 2023)

Rowe and Rankl, UK Government briefing: Housing and Net Zero (House of Commons Library, 2024)

.png)

.png)